Venus of Urbino Titian 1534 |Galleria Uffizi

The French poet Charles Baudelaire once declared: “What is art? Prostitution.” Throughout history, artists have used prostitutes as models and muses for their artwork. While this long practice has in the past been an ignored fact, some artists choose to imply or even outright declare who the subject of their work is. From Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s colourful pastels to Egon Schiele’s erotically charged sketches, here is a pick of the nine most famous artworks featuring prostitutes.

‘Venus of Urbino’ (1534) – Titian

The splendid ‘Venus of Urbino’ by Titian Vecellio is a true masterpiece, painted by the famous Venetian painter in 1538 for the Duke of Urbino Guidobaldo della Rovere. According to tradition, the beautiful woman may have represented a Venetian courtesan and in fact, her alluring look and sensuality can be easily connected to ‘an ‘expert of love.

In Venice, the phenomenon of courtesans was well tolerated even embraced and sometimes even encouraged, for fear of homosexuality.

Édouard Manet, ‘Olympia’, 1863 | Musée d’Orsay

‘Olympia’ (1863) – Édouard Manet

Manet wasn’t shy about Olympia’s profession. Olympia is explicitly a prostitute; the orchid in her hair, her black neck ribbon and the black cat at her bed are all implicit symbols of her status – even her name was associated with prostitutes. When first shown in 1865 at the Paris Salon, it caused an uproar. Parisians weren’t fazed by the nudity – it was Olympia’s cold, brazenly direct stare, the apathy set in her face, her un-voluptuous body and her disregard to the bouquet held by her servant that scandalised them. An antithesis to Titian’s sensual and enticing Venus of Urbino (1538), Manet’s Olympia confronts us with the stark reality of a woman prostituting herself. The model was Victorine-Louise Meurent, a painter in her own right and a model favoured by many artists of the time.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, ‘La Toilette’, 1889 | Musée d’Orsay

‘La Toilette’ (1889) – Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Toulouse-Lautrec was fascinated by prostitutes. He frequented the Moulin Rouge and the brothels in and about Montmartre, and he never forgot to bring his paper and materials with him. Much like Manet, he neither sexualises nor condemns prostitutes, and instead gives a rare glimpse into their everyday lives. Toulouse-Lautrec produced a whole series of pastels on the relationships he witnessed between prostitutes, sympathetically portraying their companionship without fetishising their intimate moments. La Toilette was painted sometime after his pastel series; the woman, Carmen Gaudin, was a favourite model of his. Carmen was a laundress but she prostituted herself to make ends meet. Lautrec makes allusions to this and her activities, with her overall lack of clothes apart from one loose black stocking. Like in many of Lautrec’s pieces, he captures the quiet intimacy of her routine, an almost vulnerable ‘keyhole’ peek into her life.

Vincent Van Gogh; ‘Sien With a Cigarette, Sitting on the Floor Beside the Fireplace’; 1882 | Kröller-Müller Museum

‘Sien’ series – Vincent van Gogh

When you think of Vincent van Gogh, prostitutes are probably the furthest subjects that pop into mind. His infamous self-portraits, the sunflowers or even a starry night sky are iconic to his oeuvre, yet Van Gogh did paint prostitutes. (Indeed, after his now infamous ear-chopping incident, he handed the wrapped up severed remains of his ear to a prostitute.) As a young man, he produced a series of sketches on Clasina Maria Hoornik, or Sien. When he first met her, Sien was pregnant and destitute. He took her in – much to the shock of his family – and sketched her, her daughter and later the baby boy she had over the two years or so they spent together. Sien is unabashed under Van Gogh’s scrutiny, either in her nakedness, feeding her child or even just smoking. It’s no wonder then that Van Gogh’s personal favourite was a sketch called Sorrow (1882), which remains popular to this day. Sien’s sombreness is well documented in these very early drawings.

Henri Gervex, ‘Rolla’, 1878 | Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux

‘Rolla’ (1878) – Henri Gervex

Much of Gervex’s early work was based on myth and stories, which were more often than not just an excuse to paint nude women. Rolla is no exception. He was well liked by the Salon de Paris, but they savagely rejected Rolla on the grounds of it being “immoral”. However, the resulting scandal meant that when the painting was finally exhibited a short while later, crowds rushed to see it. Gervex’s inspiration for the painting was a poem by Alfred de Musset – in this scene, the young hedonist Rolla is implied to have had sex with the teenage prostitute, Marie. Like many paintings of the late 19th century, her status as a prostitute is strongly alluded to with her undone corset and clothes, while in probably the best innuendo and allusion to sex in art history, Rolla’s cane emerges out from her discarded clothes.

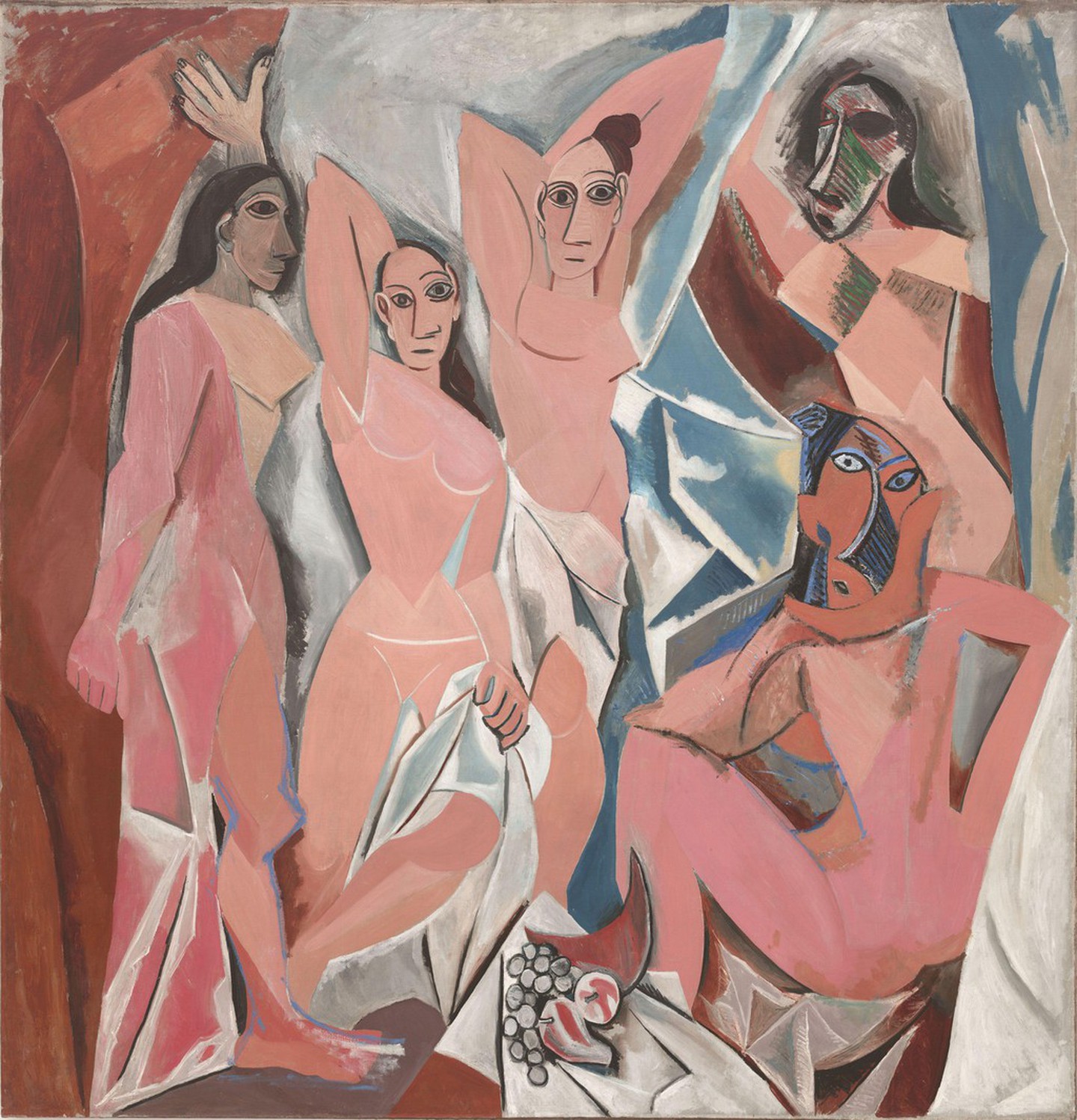

Pablo Picasso, ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’, 1907

‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’ (1907) – Pablo Picasso

Allegedly, when Picasso first heard about the shocked reaction of the public to Matisse’s Le Bonheur de Vivre (1905), with its then avant-garde aesthetic, his first thought was to outdo his rival. In 1907, he did just that. Even before the public saw it (years later, in 1916), not many of Picasso’s fellow artists liked it. Matisse, apparently, was enraged by it and called it “a bad joke”. Much like Lautrec and Manet before him, Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was less about titillation, but unlike their work, Les Demoiselles is so aggressively confrontational. The women are stripped down into 2D disjointed shapes, uncomfortably angular and devoid of traditional associations of femininity and beauty that it’s almost uncomfortable to look at them. Stylistically, Les Demosielles was influenced by Picasso’s interest in ‘Primitive’ art; three of the women’s faces are likely to be inspired by Iberian and African masks exhibited in Paris at the time.

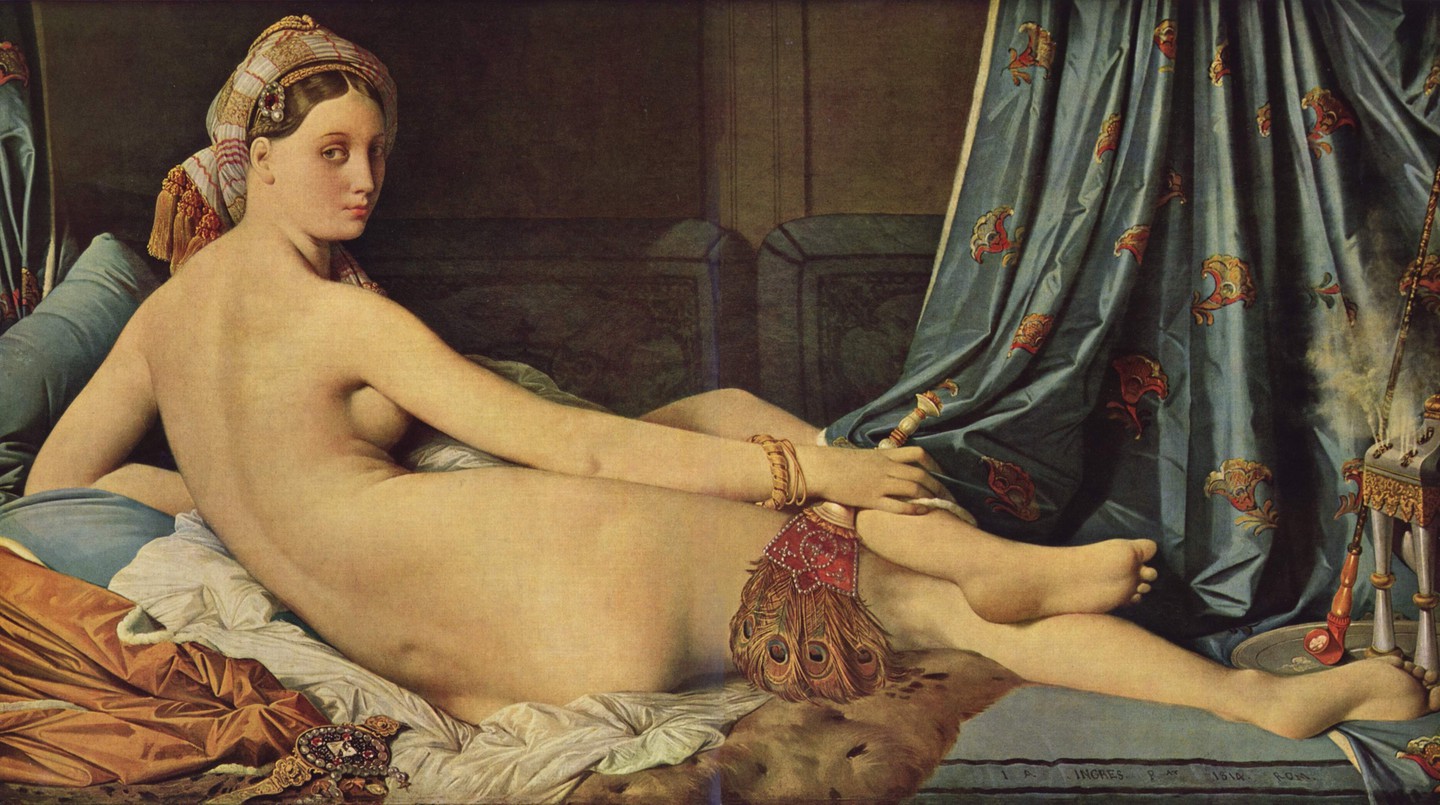

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, ‘Grande Odalisque’, 1814 | Louvre

‘Grande Odalisque’ (1814) – Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Odalisque is actually a loanword – it came from the Turkish word odalık, originally meaning a chambermaid. In the West, the word has come to solely mean a harem concubine. In a running theme for this list, Grande Odalisque by Ingres wasn’t received very well when it was first shown. But less so for its subject and more because of the exaggerated and anatomically wrong proportions of the concubine. Her long limbs and neck, small head, tiny waist but large torso were widely criticised; her pose has since been proven to be completely impossible for any real woman to do. Ingres’ purposeful disregard of anatomy was meant to show sensuality through her ‘curviness’, further propped up by her plush and opulent surroundings.

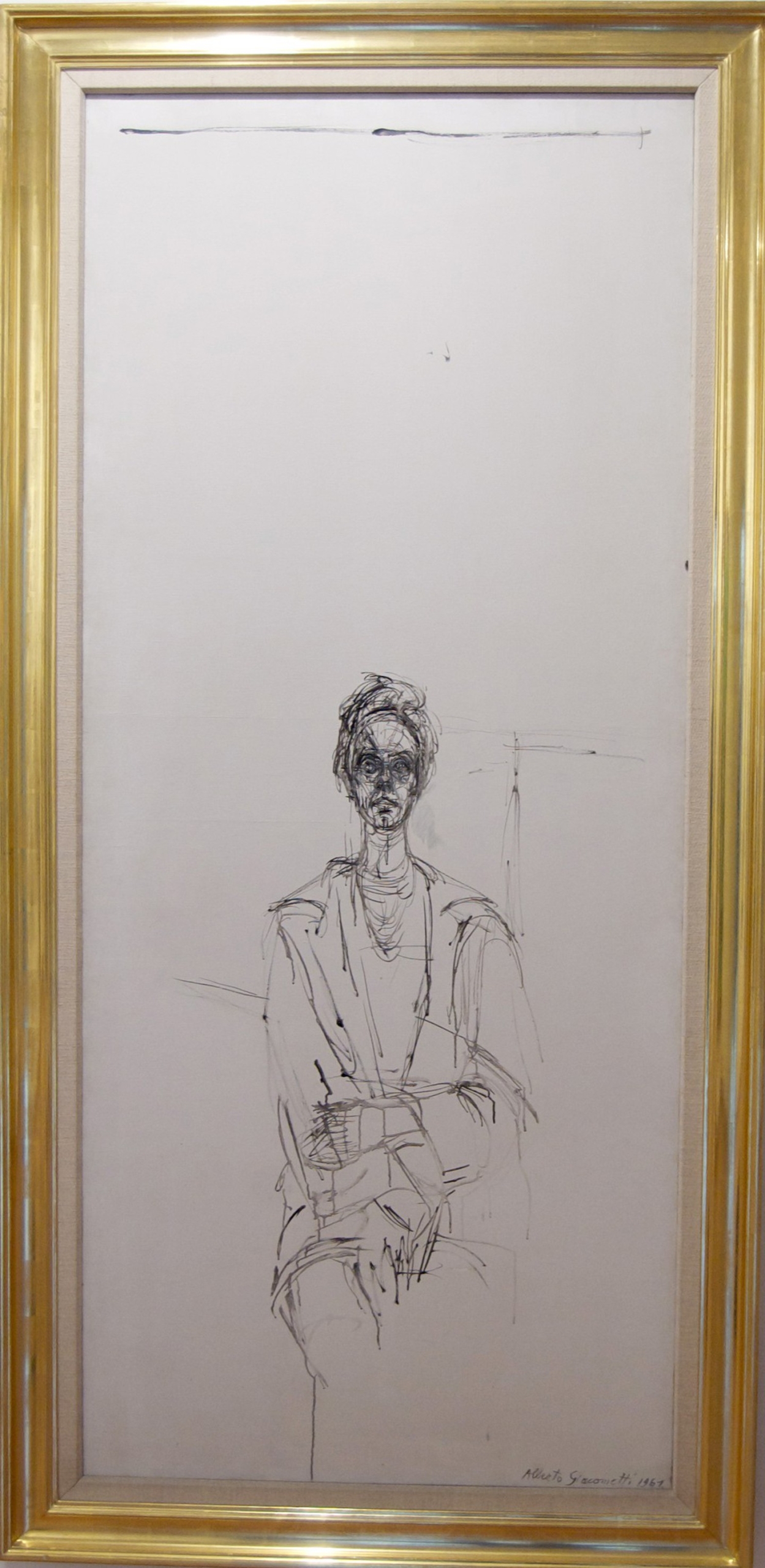

Alberto Giamotti, ‘Carolina Sobre Fondo Blanco’, 1961

‘Caroline/Carolina’ series – Alberto Giacometti

Alberto Giacometti came to define the existential post-war years of art with his thin, stick-like statues of men and women. Their whittled-down appearance made them seem far away and distant, but still human. There were many women who sat as models for Giacometti and his statues. For a long time, his favourite model was his wife, Annette. Then Giacometti met Caroline – real name Yvonne Poiraudeau – a Parisian prostitute who he may or may not have been completely infatuated with. (Annette wasn’t happy, either way). Infatuation or not, Giacometti was fascinated by Caroline and her life, and he often funded her lifestyle. In his last years, all his work focused solely on depicting her. A draftsman as well, Giacometti made a few paintings of Caroline. In all three of them, he paints her in his usual simple, sketch-like style but her face is detailed, drawing the viewer’s attention. In particular, her eyes are wide and gaze out at the spectator as if returning their own open stare. Famously, on one of them, Caroline stubbed out her cigarette while Giacometti was still painting it. The burn stain is still there to this day.

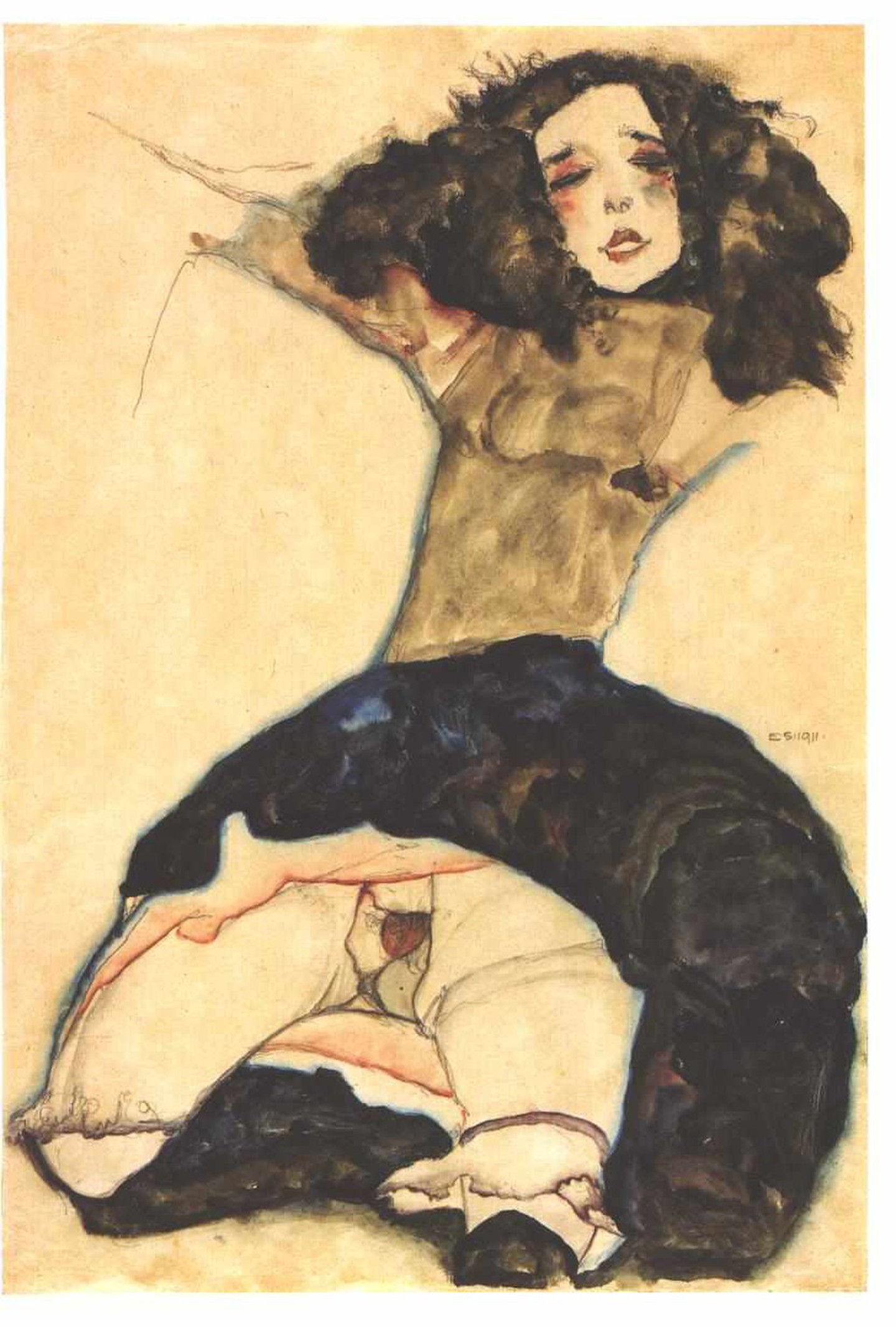

Egon Schiele, ‘Black-Haired Girl With Lifted Skirt’, 1911 | Leopold Museum

‘Black-Haired Girls’ series – Egon Schiele

Egon Schiele loved women. If Lautrec depicted prostitutes in their quiet, intimate moments, then Schiele drew all manner of women at their most erotic and open moments. But like Lautrec, Schiele viewed these women not through the male gaze but as they were, and so much of his work comes out as empowering: women are shown confident in their sexuality and desires. He was also not shy about this love. It got him into trouble on one or more occasion when he showed his sketches to pretty much anyone he could – including young girls. One of his many scandals was the Black-Haired Girls – a pair of teenage prostitutes. In most of the paintings and sketches of the pair, Schiele is explicit in the both their nudity and age; neither girls, for example, are drawn without much pubic hair, if at all. In Black-Haired Girl With Lifted Skirt (1911), he draws our attention to her exposed crotch with a bright burst of red colour – typical in many of his explicit artworks – forcing us to acknowledge her exposed nakedness. Her pose and expressions are almost grotesque in how contorted they are. If such drawings can today be considered straddling the line between art and pornography, you can imagine the scandal they caused back in the early 20th century.